Abstract

Introduction

A variety of sectors in Bangladesh have experienced large-scale development, such as agricultural processing, engineering, and finance, among others. However, the textile industry has had the greatest influence on the nation’s economy, creating jobs across a wide range of industries, fostering expansion, and thereby significantly boosting the national income. Few industries were able to keep up with the market changes that came about as a result of globalisation and increased trade freedom in their respective nations, but one of the main factors in Bangladesh’s textile industry’s success was its ability to overcome the challenges presented by globalisation and leverage it to its advantage in a way that led to significant growth over the past few decades. Bangladesh’s access to abundant cheap labour, and natural resources, as well as the proactive approach taken by its government, allowed it to become more competitive in the global market. In this article, I aim to provide a thorough account of Bangladesh’s textile history and how it was able to use certain resources to its advantage and become a global powerhouse in the textile industry today. The article further talks about the socio-economic implications of this successful transition, such as the advantages and challenges it has brought to the workforce of the nation.

The History

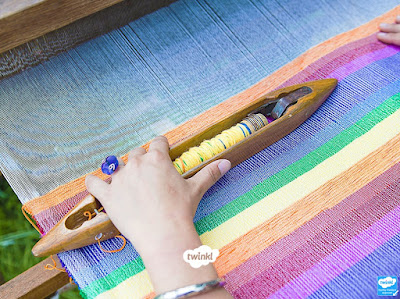

The economic lifeline of Bangladesh did not earn this title overnight, it started with the growth of the Eastern civilisation and the search for finer yarns and cotton fibres . This kind of cotton was grown in the district of Kapasia, neighbouring Dacca. The weaving of cotton in this area contributed significantly to the development of the local economy. Many wealthy families favoured the Muslin fabric and their patronage allowed for the development of new and innovative techniques that resulted in the creation of the famous Dacca Muslin. This muslin was highly sought after and became an iconic symbol of the region’s craftsmanship – largely commercialised after the establishment of the Mughal capital in Dhaka in the 17th century. Mughal rulers had a taste for fine luxurious fabrics; therefore, large quantities of Dhaka Muslin were produced for the use of emperors, queens, and noble officers. This promotion by the Mughal court helped to elevate the status of the craft as well as display its prestige for quality and beauty, making it a sought-after good in the luxury market and putting Dacca on the map as a major centre for textiles.

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Dhaka Muslin saw a huge decline in exports due to the loss of patronage from the Mughal empire as the Mughal rulers lost their power and influence. There was a subsequent decrease in demand and production, a lack of economic incentives for artisans, and a gradual decline in the industry until production eventually ceased. Another evident reason for the disappearance of muslin production was the Industrial Revolution in England. The introduction of inexpensive, mass-produced fabrics made from cotton, wool, and silk quickly made muslin obsolete. The lower prices of the new fabrics meant that consumers could not afford to buy muslin, making it difficult for Indian muslin producers to compete. Eventually, in 1800, the British government put a halt to the sale and production of muslin. This caused a major disruption in the Indian economy, and the production of muslin was quickly taken over by the British.

In 1960, Dhaka was the site of the first garment industry in Bangladesh and till 1971 the garment industries in this area were intended solely for domestic use. After liberalisation, the garment industry was 100% export-oriented due to the pioneering efforts of some entrepreneurs – Daewoo of South Korea established a joint venture with Desh Garments Ltd in 1977, which was the first export-oriented ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. One of the reasons for the growth during this period and the increasing demand from international buyers was Bangladesh’s status as a least-developed country with a large population willing to work for relatively low wages. Additionally, it did not have the same quota restrictions as other countries, making it easier for businesses to operate without having to pay additional fees.

Taking advantage of these factors, international markets like that of the US were able to strategise accordingly by relocating garment factories in such countries that had a pool of trainable cheap labour. This allowed them to sustain business practices and remain competitive in international markets. As a result, the Bangladeshi garment industry was able to offer competitive prices on clothing and textiles, which enabled them to gain a foothold in the US market and expand rapidly. This marked the beginning of a new era in the country’s economy, as the garment industry provided a much-needed boost to the country’s manufacturing sector. Currently, Bangladesh is the second-largest apparel exporter in the world, after China. The clothing industry currently houses more than 4500 factories in the country, with over 3 million workers, out of which more than 80% constitute the working woman’s population.

Opportunity cost of economic growth in Bangladesh

Agreeably, the garment industry has done wonders for the country and its people, but at what cost? Even though it’s a major employer of women, they are heavily exploited in this industry as well. When we do a comparative analysis of women’s living conditions pre-independence and pre-liberalisation in Bangladesh, we conclude that they faced several social constraints – which persist today – but they also dealt with non-existent financial freedom. The RMG sector boost vastly changed this scenario. Women actively engaged in the industry and gained socioeconomic freedom and power – they now have a voice and recognition within their households, a sense of self-worth and agency, and improved overall well-being. This improved their standing in society and aided in the empowerment of women, which in turn helped to reduce the gender disparities in the country to some extent. However, there are arguments stating that the advantageous effects of employment for women are eclipsed by unfair conditions like the wage gap, poor and irregular payments, job insecurity, gender-based violence, harassment, and unsafe working environments. This perpetuates their position at the bottom of the employment chain, where they work to meet impossible production targets, receiving wages insufficient to solely manage their households.

Not only this, but child labour has also been reported in various factories across Bangladesh despite laws against such practices. Therefore, the textile industry needs to ensure lawful practices and improve the working conditions for its staff and the provisions given to them to make these garments desirable for international buyers. These garment factories have earned the moniker of “sweatshops” indicating the exploitation of workers when nations like the USA and UK take excessive advantage of the low labour costs for their global fashion retailers like Primark, H&M, Zara, and Uniqlo. A sweatshop is generally characterised by substandard working conditions, minimal wages, and unreasonable working hours. They propagate an extremely hostile labour culture that regresses the workforce of the nation back by many decades. So, while the industry continues to drive economic growth in the country, there is a need for serious social change, considering the welfare of workers.

Contributions of the Government and the People

Following the Rana Plaza disaster, the government took steps to ensure workplace safety and labour rights by implementing minimum wage increases. The National Garment Workers Federation has also been working to set up factory-level unions to challenge labour rights violations. However, there are ongoing criticisms about the implementation and acknowledgement of these regulations as the last wage increase was in 2013, and the pro-worker strategies by the International Labour Rights Forum present in Bangladesh have been difficult to implement. This ignorance from the government stems from the intense competition Bangladesh faces from other countries for international brand orders and since the economy of the country depends on it for the majority of its exports, the government needs sweatshops to exist since losing exports to other nations has the potential to dismantle the economy.

These socio-economic and political factors contribute to the persistence of sweatshop culture not only in Bangladesh but all around the world. The workers’ conditions resonate with borderline modern-age slavery; it is a vicious cycle propagated by multinational corporations that jump from country to country in their quest to find cheaper factors of production, their only concern being their profit-loss statements. The only way to break the chain is for consumers to band together to boycott such companies – the infamous boycott of Shein – that compels them to make changes in the treatment of their workers and engage in ethical practices. Hence, there is a vital need for international pressure and consumer awareness to push for collaboration between governments, businesses, and labour organisations to act against the violation of labour rights. In conclusion, Bangladesh’s textile industry has acted as the most significant source of employment for its citizens, but several factors are causing the social decline of this industry. There is a need for Bangladesh to remove itself from this downward spiral to progress towards actual development and move forward with its economic progress.

Comments

Post a Comment